The Beast in Me opens with a woman who can no longer do the one thing the world believes she was born to do. Claire Danes plays Aggie, a Pulitzer Prize–winning author frozen in place four years after a drunk driver causes an accident resulting in the death of her young son. She stopped writing, stopped engaging, stopped living anything but the most careful, interior life. Her home in an affluent enclave outside New York City has become less a refuge than a cocoon.

Next door—though “next door” is a relative term in a neighborhood where the houses are the size of minor embassies—lives Nile, played with trademark restraint and intensity by Matthew Rhys. Years earlier, Nile’s first wife disappeared. No one ever found a body. No charges were ever filed. But the media turned him into a dark fascination, a man whose fortune and bearing made him an irresistible subject of speculation. He rebuilt his life nonetheless, now living with his second wife, played by Brittany Snow, in a home that is outwardly serene and inwardly watchful.

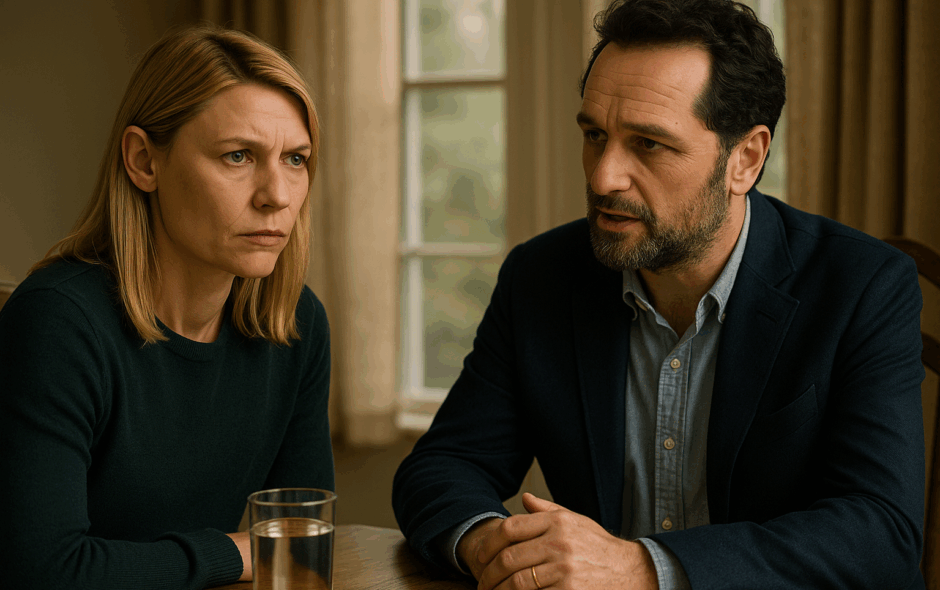

Aggie has avoided every social overture since the accident, but when Nile extends an invitation to lunch, something in her softens. She goes. Their conversation begins ordinarily enough—two well-known people who have retreated from the public eye, trying awkwardly to form a connection—but shifts when Aggie admits she’s working on a book about the unlikely friendship between Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Antonin Scalia. She can’t find her way into it. The spark isn’t there.

Nile listens, then delivers a line only someone used to being misjudged could deliver with such calm insolence: “That story’s boring. You should be writing about me. My life is far more interesting than theirs.”

It would be insufferable if Rhys didn’t ground it in something more complicated than ego. Aggie initially recoils from the remark, but it works on her the way a stone works on water—it leaves ripples. A few days later, she returns to him and says, almost accusingly, “This was your idea. Why not let me write about you?”

That uneasy proposition becomes the engine of the series. Danes plays Aggie with a kind of controlled fragility, a woman aware that one wrong emotional movement could shatter her. Rhys, meanwhile, gives Nile a quality rare in television thrillers: the presence of someone who has learned to wear suspicion like a bespoke suit. And Snow, as his second wife, plays the role with an understated alertness—someone who knows the story the world has written about her husband and watches every interaction he has with the vigilance of someone guarding forbidden territory.

The show’s tension comes not from supernatural threats but from the slow unspooling of character. Aggie wants the truth, but she also wants a narrative—something she can structure, shape, impose order on. Nile resists that instinct even as he feeds it. Their interviews feel like chess matches played with emotions instead of queens and pawns. And every exchange makes Aggie inch closer to the thing she fears most: telling a story before she fully understands the one she has lived.

The “beast” the title promises is not a creature at all but the private, buried thing each character hopes no one else will excavate. As the early episodes unfold, secrets flicker at the edges of scenes like shadows someone keeps insisting are tricks of the light.