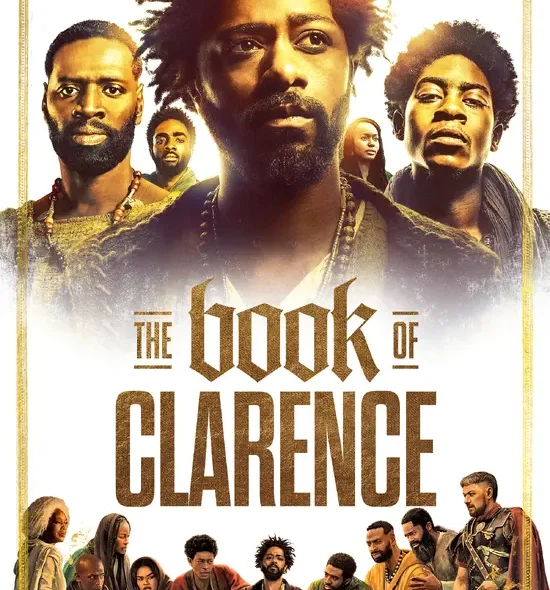

Jeymes Samuel’s The Book of Clarence is nothing if not ambitious. A brash, genre-bending reinterpretation of biblical storytelling, the film throws all convention aside to follow Clarence, played by LaKeith Stanfield, a cynical hustler in A.D. 33 Jerusalem who seizes upon the rise of Jesus to imagine himself a new Messiah—and by extension, a ticket out of debt and obscurity. The result is a film bursting with creativity and contradiction, engaging yet uneven.

Clarence is struggling—deep in debt, financially strained, morally ambiguous—and watching his apostle twin brother, Thomas, follow Jesus only fuels his resentment. Convinced the path to freedom lies in divinity, Clarence launches a sham messiah act, staging miracles with his friend Elijah and swirling in a world of deception, satire, and streetwise hustle. Stanfield shines in the role, delivering a layered performance that balances desperation and charm, giving Clarence a magnetic charisma even when his tactics are ethically dubious.

The supporting cast is stacked with talent. Omar Sy, Anna Diop, James McAvoy, Benedict Cumberbatch, and Alfre Woodard bring weight and variety to the proceedings, inhabiting apostles, Romans, and others with energy that underscores Samuel’s provocative vision of Jerusalem. Each addition to the ensemble brings a fresh shade to a story already brimming with spectacle and satire.

Visually, the film is rich and vibrant. Samuel draws from classic Hollywood epics but infuses his setting with soulful music, bold production design, and a keen cinematic energy that feels wholly modern. The soundtrack is a cultural feast, with contributions from Lil Wayne, Shabba Ranks, Doja Cat, Kid Cudi, JAY-Z, D’Angelo, and more, underscoring scenes with a vitality that defies convention and keeps the film pulsing with life.

The problem is one of tone. Samuel’s script ricochets between satire, drama, comedy, and surrealism with reckless joy, but the transitions can feel jarring. One moment Clarence is orchestrating a farce, the next the film seeks profundity. That tonal indecision undercuts the emotional and thematic beats, rendering some sequences exhilarating and others unfocused. Some viewers will find this exhilarating, others frustrating, but it undeniably makes for a singular viewing experience.

At its heart, the film grapples with faith, performance, and the hunger for recognition. Clarence’s masquerade is more than a gimmick; it is a commentary on how belief and image can become intertwined, and how desperation can fuel self-deception. Samuel’s approach reimagines the biblical epic through a Black, contemporary lens, and in doing so he revives a genre that had grown stale, even if his methods are messy. The film is never dull, even when its ambition outpaces its coherence.

Despite its boldness and high-profile cast, The Book of Clarence struggled at the box office, grossing around six million dollars against a forty million dollar budget. Critical and audience reception was polarized, with some praising its visual style and audacity while others dismissed it as scattershot and unfocused. It has already found a cult following, however, among those who appreciate its daring blend of satire and spirituality.

In the end, The Book of Clarence is a visual and thematic feast—beautifully shot, musically rich, and undeniably original. LaKeith Stanfield anchors the story with charisma and complexity, while Samuel’s direction reverberates with creative energy. Yet the film’s refusal to commit tonally—a chaotic jumble of faith, farce, and drama—keeps it from coalescing into a fully satisfying experience. For those craving something different, irreverent, and visually striking, it is worth the journey, even if its destination is left deliberately ambiguous.