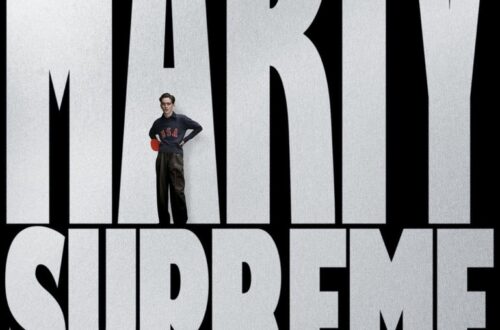

Steve opens one morning in the mid-1990s at a “last-chance” reform school perched on the edge of a rural landscape. The campus grounds are tired—peeling paint, flickering lights, worn uniforms—and at the centre of it all stands Steve, played by Cillian Murphy, who has stepped into the role of headteacher with an unshakable resolve: keep the doors open, keep the boys in line, keep hope alive. As the day progresses, one after another his carefully laid plans begin to fray.

Steve is adapted from Shy by Max Porter, and directed by Tim Mielants. It shifts the narrative perspective away from the students and places it firmly on the adult who tries to hold things together. Steve would rather not admit how much he depends on this job for purpose, but cracks are showing—in his glasses, his voice, the way his hand trembles when he writes behaviour reports.

When a documentary crew arrives to profile the school, their presence emits a silent threat. What was meant to paint the institution in a favourable light begins to edge toward exposure. Steve knows how fragile the school is, and he knows its margin for error has vanished. One boy is more volatile than the others; whispers of the staff’s failure to save him drift through the corridors. Steve watches the maps unfold: funding cuts, staffing exhaustion, media glare. The students do what students do—they test every boundary, form alliances, break rules, unleash pent-up frustration. Steve watches too, sometimes powerless.

Murphy inhabits the role with such rawness that at times you forget you’re watching an actor. A beard flecked with grey, a wardrobe of sagging shirts and old ties, a voice that cracks before it holds itself together. We see him in the staff room, listening to complaints, in the classroom attempting to reach a young man whose eyes are locked on escape, and alone in his car at night, rummaging through his keys, trying to push off the day that will never leave him. The script allows him little respite; the camera seldom lets him turn away.

A sequence near the end delivers a quiet storm. Steve enters the boys’ dorm after hours, finds a fight, intervenes, and in the aftermath sits with one student who refuses to speak. The silence between them is heavy. Steve doesn’t know what to say; the boy doesn’t know how to ask. It is an uncomfortable scene, a testament to the trust—and distance—that defines the place.

While the film never shies from its bleak subject, it refrains from complete despair. Steve holds onto a ramshackle hope: a book donation, a teacher who stays late, a boy who keeps showing up. What matters is the looking-up after the fall, the decision to stand again. In a modest running time the film becomes a small epic of institutional failure and personal endurance.

For Murphy this is a bold move. Fresh off major roles, he strips away the polish and allows Steve to be tired, disillusioned, human. The supporting cast—boys with anger and confusion, teachers with worn smiles—provides texture. The setting, a school on the brink, becomes almost a character, breathing exhaustion, threat and possibility.

Steve is not an easy watch. It makes you squirm in its moral corners, wonder where the adults are when they depart, and leave you with an image of a man staring at a corridor full of doors he can’t fully open. But it lingers. And in Murphy’s performance you find a portrait of someone battling against the closing of his world. In that fight, there is dignity, however battered.

If you’re drawn to character-driven drama, to stories of people working the seams of broken systems, Steve may be one of the year’s most quietly devastating films.