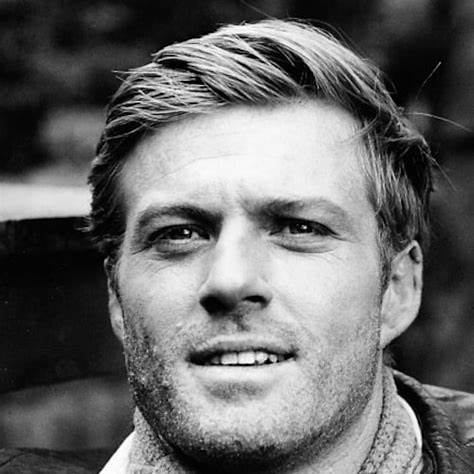

When Robert Redford died at his home in Utah at the age of 89, the world did not simply lose an actor, director, and environmentalist. We lost a man who, in his quiet way, taught us how to balance beauty with responsibility, charm with conscience, and stardom with substance. For us — Lisa Johnson Mandell and Tandy Culpepper — his life and career carry special resonance, both as film critics and as people who admired the way he used his influence to build something lasting. This is a love letter to a man who shaped American cinema and reshaped American culture.

Redford first captivated audiences with his golden locks and a charisma that seemed effortless. Hollywood has never lacked handsome men, but few combined glamour with intelligence as naturally as he did. His breakout in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid alongside Paul Newman made him a star of global proportions. The image of Redford as the Sundance Kid — sly, understated, forever glancing sideways at his fate — would follow him for the rest of his life. But Redford himself was never content to coast on charm. He knew that charm fades unless anchored to something deeper.

In the 1970s, he pursued roles that spoke to the anxieties of the age. The Candidate exposed the hollowness of modern politics, Three Days of the Condor distilled Cold War paranoia into a human story, and All the President’s Men gave us a determined Bob Woodward, bent over a typewriter as history unfolded. These films were not just entertainments; they were cultural documents, mirrors to an America wrestling with its conscience. And then there was The Way We Were. Opposite Barbra Streisand, Redford revealed a vulnerability that only deepened his allure. The contrast between his reticent stillness and her fiery conviction created one of cinema’s most beloved romances.

What made him unique was not only his choice of roles but the way he played them. He was the thinking person’s leading man. He often paused before speaking, giving audiences a glimpse of the conflict beneath the polished surface. His characters seemed to know that moral certainty was a luxury, and that indecision could be as heroic as boldness. He invited us into that hesitation, into the humanity of uncertainty.

His ambitions eventually carried him behind the camera. When Ordinary People premiered in 1980, few expected that Redford — the movie star — would deliver such a delicately devastating portrait of family grief and repression. Yet he did, and Hollywood responded with Oscars for both Best Picture and Best Director. The win proved what many had suspected: his artistry was not limited to the screen. Films such as A River Runs Through It and Quiz Show followed, directed with patience, restraint, and a deep respect for character.

But Redford’s greatest directorial effort was not a film. It was the creation of Sundance. In 1981, he founded the Sundance Institute, giving filmmakers a place to experiment away from the pressures of studios. From that grew the Sundance Film Festival, which by the 1990s had become the heartbeat of American independent cinema. Entire careers — Steven Soderbergh, Quentin Tarantino, Ava DuVernay, Chloe Zhao — trace their roots to the stages Redford built in the Utah mountains. Sundance was more than a festival. It was a revolution in how films were made, discovered, and shared. And it was Robert Redford’s vision that made it possible.

Outside the world of film, he was just as committed. Decades before it was fashionable for celebrities to champion environmental causes, Redford was using his platform to protect public lands and advocate for clean air and water. His bond with the American West was more than aesthetic. It was spiritual. He did not see the mountains and deserts as scenery but as sacred trust, and he devoted his voice and resources to their preservation. That commitment was consistent, visible, and woven into the very fabric of his life.

The awards came, as they inevitably would: the Academy Award, the Kennedy Center Honors, the Presidential Medal of Freedom. But those who knew him always sensed his discomfort with accolades. He preferred to talk about other people, other projects, the next idea. Recognition was a byproduct; creation was the point. And in creating Sundance, he created opportunities for thousands.

Redford’s beginnings, too, shaped him. Born Charles Robert Redford Jr. in Santa Monica in 1936, he once considered himself a drifter — an art student who wandered Europe before stumbling into acting. That sense of curiosity, of restlessness, never left him. He started on stage, graduated to television, then film, always balancing discipline with a bohemian streak. The career that followed lasted six decades, with triumphs in thrillers, romances, political dramas, and late-life experiments. One of his last great roles, in All Is Lost, featured almost no dialogue — just Redford alone on a boat, fighting for survival. It was a summation of his art: stripped of everything but presence, he remained magnetic.

For us, the lasting images come in fragments. Redford hunched over a typewriter as Woodward, piecing together Watergate. Redford as the Sundance Kid, laughing as he leaps off a cliff. Redford holding Streisand, their love undone by forces larger than themselves. Redford alone at sea, wordless yet eloquent. In these moments, he gave us more than entertainment; he gave us reflections of ourselves.

As colleagues in film criticism, we feel both loss and gratitude. We admired not only the artist but the architect: the man who turned stardom into stewardship, who used privilege to open doors for others. Robert Redford’s absence leaves a void, but his influence surrounds us — in the independent films that continue to challenge convention, in the environmental protections he fought to secure, in the idea that celebrity can be a tool for service.

Goodbye, Robert Redford. Thank you for the films, the festival, the inspiration. Thank you for reminding us that to be golden is not enough — one must also be generous. Your legacy lives on in every artist you nurtured, every story you believed in, every landscape you protected. You will be missed, but you will not be forgotten.

With deep respect and affection,

Lisa Johnson Mandell & Tandy Culpepper