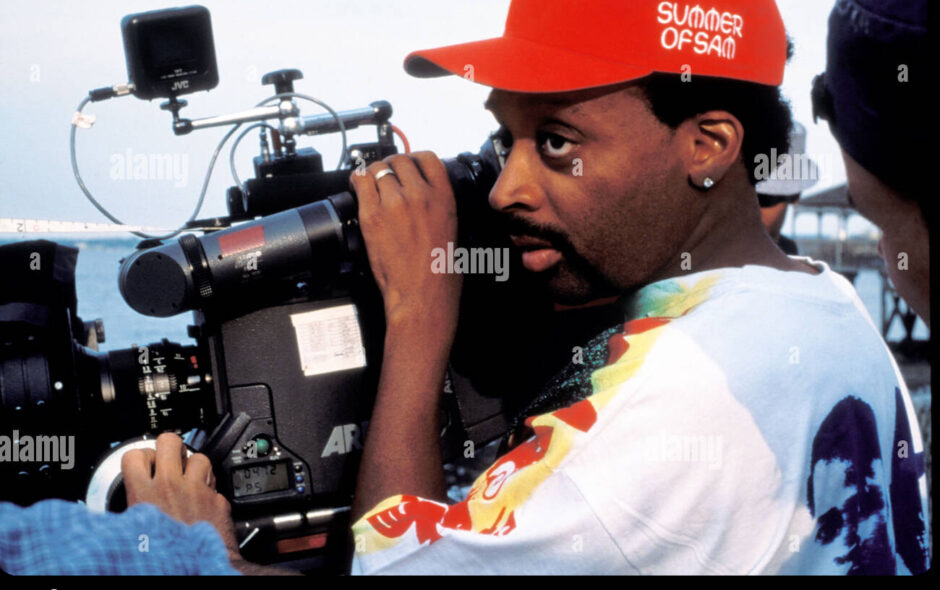

For nearly four decades, Spike Lee has been a voice impossible to ignore. His films, his persona, and his unmistakable presence—whether on stage at Cannes in a purple suit, courtside at Madison Square Garden in Knicks orange, or behind the camera shouting “Action!”—have made him one of the most distinctive and enduring figures in American cinema. With the abrupt cancellation of his Colin Kaepernick docuseries at ESPN, Lee once again finds himself at the center of a cultural clash, reminding audiences why he has been both celebrated and controversial since the start of his career.

Born Shelton Jackson Lee in Atlanta in 1957 and raised in Brooklyn, Lee came of age during the upheavals of the 1960s and 1970s, surrounded by the jazz, politics, and neighborhood dynamics that would later fuel his films. After studying mass communication at Morehouse College and film at NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts, he emerged with a thesis film that turned heads: Joe’s Bed-Stuy Barbershop: We Cut Heads (1983), which won a student Academy Award. From the start, Lee’s themes were clear—race, community, and the collision of history with contemporary struggle.

He broke through nationally with She’s Gotta Have It (1986), a low-budget black-and-white film shot in two weeks that became a box-office success. Its frank exploration of sexuality and independence was groundbreaking, and it introduced the world to the distinctive Spike Lee aesthetic—bold visuals, jazzy pacing, and dialogue that captured both the humor and the tension of Black urban life.

Lee’s early films quickly established him as an auteur with a singular voice. School Daze (1988) took on colorism and class divisions within Black communities. Do the Right Thing (1989), widely regarded as his masterpiece, dramatized a sweltering day in Brooklyn that escalates into a racially charged riot. Released the same year as Driving Miss Daisy, which won the Oscar for Best Picture, Do the Right Thing was not even nominated in that category—an omission that symbolized Hollywood’s discomfort with Lee’s blunt honesty. Yet over time the film has been canonized as one of the greatest American films ever made.

Throughout the 1990s, Lee tackled subjects others avoided. Malcolm X (1992), with Denzel Washington in a career-defining performance, brought the life of the Black nationalist leader to the screen with grandeur and urgency. Crooklyn (1994) and Clockers (1995) reflected family life and inner-city crime with his signature mix of heart and tension. He Got Game (1998) explored sports, fame, and fatherhood, starring Washington opposite NBA star Ray Allen.

Lee’s work has always been both prolific and eclectic. He moves from intimate indie films to studio projects, from documentaries to commercials. His documentaries—4 Little Girls (1997), about the Birmingham church bombing, and When the Levees Broke (2006), about Hurricane Katrina—show his ability to blend artistry with journalistic urgency. His fiction films often combine satire with social critique, as in Bamboozled (2000), which skewered television’s exploitation of racial stereotypes, and Chi-Raq (2015), which reframed Greek tragedy to comment on gun violence in Chicago.

Recognition from Hollywood has come slowly but steadily. He won his first competitive Oscar in 2019 for Best Adapted Screenplay for BlacKkKlansman, his fact-based story about a Black detective infiltrating the Ku Klux Klan in the 1970s. By then, he had already received an honorary Academy Award, but the competitive win was vindication. At Cannes, where he has long been a fixture, he served as jury president in 2021, further cementing his stature on the international stage.

Lee’s career is not defined by awards alone. He is as much a public intellectual as a filmmaker, a man whose Knicks fandom, outspoken politics, and refusal to soften his message have made him a figure of constant debate. He has taught at NYU for decades, mentoring new generations of filmmakers. His production company, 40 Acres and a Mule Filmworks, has become synonymous with Black independent cinema.

The aborted Colin Kaepernick docuseries fits squarely into his lifelong mission: telling stories of race, protest, and America’s struggle to reconcile its ideals with its realities. Lee has long been drawn to real figures whose lives dramatize the fight for justice. Malcolm X, the victims of Katrina, the martyrs of Birmingham—all have found their way into his lens. Kaepernick, whose NFL protest against police brutality ignited one of the most polarizing debates in modern sports, is a natural subject for Lee’s sensibilities. The project’s cancellation speaks less to his willingness to tackle hard subjects than to the difficulty of fitting them into corporate structures wary of controversy.

Lee himself has brushed off the setback with his usual bluntness, telling reporters only, “It’s not coming out. That’s all I can say.” The brevity underscores a career’s worth of lessons: he knows some fights are worth waging in the open, others behind closed doors. But no one doubts that Lee will return with another story, another film, another provocation. He always does.

Now in his late sixties, Lee remains as prolific as ever. His latest film, Highest 2 Lowest, has drawn strong notices, and his name still attracts top talent. Actors from Denzel Washington to Samuel L. Jackson, from John David Washington to Adam Driver, have flourished in his films. His style—signature double-dolly shots, bold color palettes, musical interludes—is instantly recognizable. Yet it is his voice, equal parts celebratory and confrontational, that defines his legacy.

Spike Lee is not merely a filmmaker but a chronicler of America’s ongoing racial and cultural reckoning. Whether on the screen, in the classroom, or on the streets of Brooklyn, he has never stopped asking hard questions. With or without ESPN, he is certain to keep doing so.